Today's one of the nicest days I've seen in Beijing. The sky's unusually clear today; not that I can see the sky, but at least I can see buildings in the neighborhood. In the picture at right you can see mountains in the distance; generally the two square towers near the middle of the picture are hard to see through the fog. As nice a day as today calls for being outside, so I decided to take a considerable detour on my way to the gym, and bike by the Olympic compound. As the big day gets closer and closer, every day new Olympic banners, signs, and security checks appear on campus. These days there are three checkpoints between my dormitory and the classrooms, and every lamppost I've seen lately carries a banner with the Olympic motto in Chinese or English. But as they say here, 百闻不如一见, so I'll go ahead and give you the pictures. Today's one of the nicest days I've seen in Beijing. The sky's unusually clear today; not that I can see the sky, but at least I can see buildings in the neighborhood. In the picture at right you can see mountains in the distance; generally the two square towers near the middle of the picture are hard to see through the fog. As nice a day as today calls for being outside, so I decided to take a considerable detour on my way to the gym, and bike by the Olympic compound. As the big day gets closer and closer, every day new Olympic banners, signs, and security checks appear on campus. These days there are three checkpoints between my dormitory and the classrooms, and every lamppost I've seen lately carries a banner with the Olympic motto in Chinese or English. But as they say here, 百闻不如一见, so I'll go ahead and give you the pictures. |

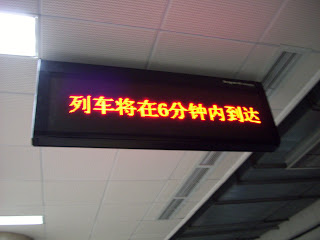

This sign appeared over the back gate to campus yesterday. The Olympics don't even need to be mentioned; the motto speaks for itself. Neither does there need to be a connection between the back gate of the Language University and the Olympic Games. The entire country is on board for the Olympics, and no area of life is safe from this slogan, from the Fuwa, or from that truly unbearable song "Beijing Welcomes You." |

The gym on campus is still cordoned off for the Olympics, but it's been downgraded. It's now the practice venue for the Special Olympic basketball teams. This hasn't reduced the amount of security checks or guards on duty, but everyone seems a bit more relaxed now; sometimes if I'm carrying groceries the guards will even let me pass without showing ID. The gym on campus is still cordoned off for the Olympics, but it's been downgraded. It's now the practice venue for the Special Olympic basketball teams. This hasn't reduced the amount of security checks or guards on duty, but everyone seems a bit more relaxed now; sometimes if I'm carrying groceries the guards will even let me pass without showing ID. |

All major roads in Beijing, and minor roads adjacent to Olympic venues, have had one lane reserved for Olympic venues. Zhixin Lu, at right, is only four lanes across to begin with, so traffic can get pretty bad. The government has attempted to reduce traffic by allowing only even-numbered license plates on the road on even-numbered days, and odd plates on odd days, but with half of many roads reserved for government officials, traffic can be as bad as ever. All major roads in Beijing, and minor roads adjacent to Olympic venues, have had one lane reserved for Olympic venues. Zhixin Lu, at right, is only four lanes across to begin with, so traffic can get pretty bad. The government has attempted to reduce traffic by allowing only even-numbered license plates on the road on even-numbered days, and odd plates on odd days, but with half of many roads reserved for government officials, traffic can be as bad as ever. |

At left is a cart built around an oversized tricycle, ridden many thousands of kilometers from Kunming by an Olympic enthusiast who has dyed his hair in the colors of the Olympic rings and had the official logos of all the Olympic events tatooed along both arms. From the little medallions atop each side of the cart, Chairman Mao looks down favorably on the whole thing; however silly Chinese support for the Olympics can get, it's nothing compared to what happened in his time. At left is a cart built around an oversized tricycle, ridden many thousands of kilometers from Kunming by an Olympic enthusiast who has dyed his hair in the colors of the Olympic rings and had the official logos of all the Olympic events tatooed along both arms. From the little medallions atop each side of the cart, Chairman Mao looks down favorably on the whole thing; however silly Chinese support for the Olympics can get, it's nothing compared to what happened in his time. |

And here's the stadium, looking a lot smaller than it actually is; in person it's as impressive today as it was when shrouded in fog. I would have liked to get a better picture, but there's no way I would be let into the Olympic Park. For 10 more days, ordinary people like this Foreign Devil will have no choice but to stand at the fence and gawk. And here's the stadium, looking a lot smaller than it actually is; in person it's as impressive today as it was when shrouded in fog. I would have liked to get a better picture, but there's no way I would be let into the Olympic Park. For 10 more days, ordinary people like this Foreign Devil will have no choice but to stand at the fence and gawk. |

Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Olympic Mania

Monday, July 28, 2008

拍马屁

The title of this post is one of those wonderfully expressive and inexplicable Chinese turns of phrase. It means "toadying" or "flattering one's superior," but its literal meaning is to "pat the horse's rump." Usually that's not my style, but I've discovered that my blog has been unbanned by the censors of the People's Republic of China, and I want to keep it that way. So:

胡锦涛是个真了不起的人。

中国队肯定会赢得每枚奥运金牌。

我一心支持中央政府的互联网政策。

If you're curious, Google will be happy to explain.

Sunday, July 27, 2008

At the Forbidden City

Here I am, squinting a bit, in the Forbidden City. I had often been warned that the Forbidden City was unbearably hot, but since I had already got up for church, and since today's especially bad pollution ought to shade the sun a little, I decided to head over there on my own. It was a very bright day, despite the haze, and very hot too. The picture above, taken by an obliging kid I trusted with my camera, doesn't show what a sweaty mess I was this morning. But the Forbidden City is the Forbidden City. The Chinese actually don't call it that anymore: its former name, 紫禁城——the Purple Forbidden City, has been replaced with the somewhat more pedestrian 故宫——the Old Palace.

Here I am, squinting a bit, in the Forbidden City. I had often been warned that the Forbidden City was unbearably hot, but since I had already got up for church, and since today's especially bad pollution ought to shade the sun a little, I decided to head over there on my own. It was a very bright day, despite the haze, and very hot too. The picture above, taken by an obliging kid I trusted with my camera, doesn't show what a sweaty mess I was this morning. But the Forbidden City is the Forbidden City. The Chinese actually don't call it that anymore: its former name, 紫禁城——the Purple Forbidden City, has been replaced with the somewhat more pedestrian 故宫——the Old Palace. Tourists can only see a portion of the city; now and then I would peek through the crack of a locked gate and see alleys and passages stretching off into the haze, the pavements overrun with as rich a carpet of weeds as any of the rugs in the great ceremonial halls. Whether intended by the Party officials in charge or not, there's a melancholy feeling about the whole place, more than anywhere else in the exhibits given over to the unfortunate last emperor Puyi; although much of my sympathy for him was lost when I leafed through his English-language memoirs in a gift shop and found him luridly praising the Communists. The Forbidden City everywhere hints at a decline: peeling paint and crumbling pavement and gutted treasuries all hint, like an empty church or decaying palace in Europe, at a cultural heritage that the present can't manage to equal. I am as big a fan of the Olympic constructions as any Chinese nationalist; but when you have something like the Forbidden City in town, a few new awe-inspiring buildings really just aren't enough.

Tourists can only see a portion of the city; now and then I would peek through the crack of a locked gate and see alleys and passages stretching off into the haze, the pavements overrun with as rich a carpet of weeds as any of the rugs in the great ceremonial halls. Whether intended by the Party officials in charge or not, there's a melancholy feeling about the whole place, more than anywhere else in the exhibits given over to the unfortunate last emperor Puyi; although much of my sympathy for him was lost when I leafed through his English-language memoirs in a gift shop and found him luridly praising the Communists. The Forbidden City everywhere hints at a decline: peeling paint and crumbling pavement and gutted treasuries all hint, like an empty church or decaying palace in Europe, at a cultural heritage that the present can't manage to equal. I am as big a fan of the Olympic constructions as any Chinese nationalist; but when you have something like the Forbidden City in town, a few new awe-inspiring buildings really just aren't enough. In the old days, of course, there were feasts and pleasure gardens and armies of eunuchs and concubines waiting on the emperor's every need, but the life of an Emperor of all China doesn't seem to have been all that enjoyable. In room after room of the Forbidden City, here in the Hall of Middle Harmony, the Emperor would have been trussed up in ceremonial robes while all sorts of obscure rites were conducted. The emperor was not really thought of as a god, as far as I know, but he had religious duties as well as political. A sign on a minor building pointed out that Chongzhen, the tragic last emperor of the Ming, had retreated there to fast in reparation for natural disasters that struck China during his reign. Overally, the layout of the city, designed as it is for ceremonial processions and large-scale rituals, reminded me a bit of the Vatican, at least until I stumbled upon the concubines' quarters. Each major concubine had a small palace of her own; I got lost in the 后宫 or Imperatricial Palace and think I found my way into every concubine's quarters before I found the way out. Except for the names over the gates (in Chinese and Manchu, a reminder that the Qing rulers were not themselves Chinese), every alley and court in the palace is more or less identical, an obession for hierarchy and order playing itself out over yellow-roofed acre after yellow-roofed acre.

In the old days, of course, there were feasts and pleasure gardens and armies of eunuchs and concubines waiting on the emperor's every need, but the life of an Emperor of all China doesn't seem to have been all that enjoyable. In room after room of the Forbidden City, here in the Hall of Middle Harmony, the Emperor would have been trussed up in ceremonial robes while all sorts of obscure rites were conducted. The emperor was not really thought of as a god, as far as I know, but he had religious duties as well as political. A sign on a minor building pointed out that Chongzhen, the tragic last emperor of the Ming, had retreated there to fast in reparation for natural disasters that struck China during his reign. Overally, the layout of the city, designed as it is for ceremonial processions and large-scale rituals, reminded me a bit of the Vatican, at least until I stumbled upon the concubines' quarters. Each major concubine had a small palace of her own; I got lost in the 后宫 or Imperatricial Palace and think I found my way into every concubine's quarters before I found the way out. Except for the names over the gates (in Chinese and Manchu, a reminder that the Qing rulers were not themselves Chinese), every alley and court in the palace is more or less identical, an obession for hierarchy and order playing itself out over yellow-roofed acre after yellow-roofed acre.  After I had seen enough of the Forbidden City (including the very pleasant Imperial Flower Garden where I completely forgot I had a camera), I decided to head out to Tiananmen Square for a walk, since I had never seen the place by day. Even since I passed through on my way to the Forbidden City, new banners, trees, and displays had been set up to welcome the Olympics. "The Five Continents and Four Seas Celebrate the Olympic Festivities," proclaims the banner at left, using a classically Chinese idiom referring to the whole world; to its right an incomplete banner was getting ready to praise the policies of the Party. Elaborate displays of trees and flowers had sprung up, where a few days before the plaza was paved straight across. The days of Confucian ritual may be gone, but the rulers of China can still pull off pomp and circumstance if they feel a need for it.

After I had seen enough of the Forbidden City (including the very pleasant Imperial Flower Garden where I completely forgot I had a camera), I decided to head out to Tiananmen Square for a walk, since I had never seen the place by day. Even since I passed through on my way to the Forbidden City, new banners, trees, and displays had been set up to welcome the Olympics. "The Five Continents and Four Seas Celebrate the Olympic Festivities," proclaims the banner at left, using a classically Chinese idiom referring to the whole world; to its right an incomplete banner was getting ready to praise the policies of the Party. Elaborate displays of trees and flowers had sprung up, where a few days before the plaza was paved straight across. The days of Confucian ritual may be gone, but the rulers of China can still pull off pomp and circumstance if they feel a need for it.  I walked a little farther, to the very south of the square, where I could catch a train back home at the Qianmen subway stop. Right above the station is the Qian Men, the Fore Gate of the ancient wall. Mao demolished the walls and used their paths for roads and subways, and the roads live on in the names of subway stops, most of which end in -men, meaning Gate. The Qian Men and a few other places were important enough to preserve, and the traffic in this city would be even worse if there were massive stone walls everywhere, but like the weeds that find homes on the roofs of the Forbidden City, the unnaturally truncated walls on either side of the Qian Men hint at something that's been lost. But it's hard to be melancholic in Beijing for long; the city just won't let you. The walls may have been demolished, but three new subway lines opened last week; the emperors may have been laid low by European gunpower and internal disorder, but it's an Olympic year. Every third person I saw on Tiananmen Square, excluding the legions of Olympic volunteers, had some bit of clothing on celebrating the Olympics. They may no longer bring tribute to furnish the palace, but the Five Continents and Four Seas are converging on Beijing again, and everybody in Beijing knows it.

I walked a little farther, to the very south of the square, where I could catch a train back home at the Qianmen subway stop. Right above the station is the Qian Men, the Fore Gate of the ancient wall. Mao demolished the walls and used their paths for roads and subways, and the roads live on in the names of subway stops, most of which end in -men, meaning Gate. The Qian Men and a few other places were important enough to preserve, and the traffic in this city would be even worse if there were massive stone walls everywhere, but like the weeds that find homes on the roofs of the Forbidden City, the unnaturally truncated walls on either side of the Qian Men hint at something that's been lost. But it's hard to be melancholic in Beijing for long; the city just won't let you. The walls may have been demolished, but three new subway lines opened last week; the emperors may have been laid low by European gunpower and internal disorder, but it's an Olympic year. Every third person I saw on Tiananmen Square, excluding the legions of Olympic volunteers, had some bit of clothing on celebrating the Olympics. They may no longer bring tribute to furnish the palace, but the Five Continents and Four Seas are converging on Beijing again, and everybody in Beijing knows it.Tuesday, July 22, 2008

理发

Yalies may recognize the title of this post from the sign that always stands outside Gourmet Heaven, announcing that haircuts can be had on the second floor. I went and got my hair cut across the street from my dorm today. I cut it short enough that it doesn't curl; I've gotten sick of Chinese people rubbing it, and when a cabbie asked me what sort of product I used to curl it, it was really the last straw.

Now all this wouldn't be grounds for a blog post, except that a professor from the university showed up and took pictures of me before and after the haircut. Apparently a forthcoming Chinese textbook includes a dialogue at a barbershop, and for a textbook designed for foreigners, it seems that only pictures of laowai would do. So in the future, students learning Chinese may get to see my lovely head of halfway-cut hair on the pages of their textbooks.

Now all this wouldn't be grounds for a blog post, except that a professor from the university showed up and took pictures of me before and after the haircut. Apparently a forthcoming Chinese textbook includes a dialogue at a barbershop, and for a textbook designed for foreigners, it seems that only pictures of laowai would do. So in the future, students learning Chinese may get to see my lovely head of halfway-cut hair on the pages of their textbooks.

Friday, July 18, 2008

Simatai Revisited

The first time I went to Simatai, it was as one of the tourists who descend on the place in droves and disappear never to be seen again. This time, staying in the village for a week, I got to know the place better: my full report will be up on the blog when it's finished. For now, some pictures of the trip will have to do:

We went up to Simatai by rail, riding in a truly ancient train car through the Chinese countryside. I slept through most of the ride——I'd spent the night before learning Chinese dice games, and I'd got up at 5 to catch the train——but I was awake long enough to see some incredible views of the great wall from the train.

After settling into our rooms in Simatai, we begain our visits to the nearby villages. The first one we visited was Jijiaying, which in ancient times was a military garrison and still has most of its original gates. The impression a place like this gives is one of age——ancient peasants hobbling past ancient cottages; and the villages are aging. The youth have mostly left for Beijing, and however many satellite dishes and telephone wires may be set up in the villages are not enough to give one hope for their future.

After settling into our rooms in Simatai, we begain our visits to the nearby villages. The first one we visited was Jijiaying, which in ancient times was a military garrison and still has most of its original gates. The impression a place like this gives is one of age——ancient peasants hobbling past ancient cottages; and the villages are aging. The youth have mostly left for Beijing, and however many satellite dishes and telephone wires may be set up in the villages are not enough to give one hope for their future.

Jijiaying may be ancient and its villagers may be graying, but the ideal of modernity has a powerful appeal there. In the local offices of the Communist Party, a shuzi yingyuan——"digital theater"——had been set up for the villagers to watch DVDs. And through a window of a storage room in the offices, I saw this thing, a 投票箱 or ballot box. Village government in China is very democratic——China has no problem with democracy making local and unimportant decisions——but even here the Party branch secretary has the last word.

Jijiaying may be ancient and its villagers may be graying, but the ideal of modernity has a powerful appeal there. In the local offices of the Communist Party, a shuzi yingyuan——"digital theater"——had been set up for the villagers to watch DVDs. And through a window of a storage room in the offices, I saw this thing, a 投票箱 or ballot box. Village government in China is very democratic——China has no problem with democracy making local and unimportant decisions——but even here the Party branch secretary has the last word.

We next visited Sujiayu Village, where we spent a while pretending we could understand the accents of a few old men we tried to interview. Even an hour out of Beijing, you can hear local accents even our teacher couldn't understand. I did understand the man who kept offering me youtiao (a sort of oily and unsweetened flaccid churro) until I accepted; and I understood the three girls who fled behind a grindstone shouting "Foreigner!" when I came to their part of the village. I stuck around, and they got used to me enough to let me take their picture.

We next visited Sujiayu Village, where we spent a while pretending we could understand the accents of a few old men we tried to interview. Even an hour out of Beijing, you can hear local accents even our teacher couldn't understand. I did understand the man who kept offering me youtiao (a sort of oily and unsweetened flaccid churro) until I accepted; and I understood the three girls who fled behind a grindstone shouting "Foreigner!" when I came to their part of the village. I stuck around, and they got used to me enough to let me take their picture.

...and much to the entertainment of the villagers, sent his American guests out to fetch water.

We went up to Simatai by rail, riding in a truly ancient train car through the Chinese countryside. I slept through most of the ride——I'd spent the night before learning Chinese dice games, and I'd got up at 5 to catch the train——but I was awake long enough to see some incredible views of the great wall from the train.

I had dozed off again when I woke up at a station stop, to the sound of Chinese drums and the sight of villagers decked out in traditional costumes. In a propaganda exercise for the Olympic Games, the official logo had been carved into the side of a mountain, and a crowd had been gathered to celebrate down in the village. I would have liked to take more pictures, but the train was on its way again, and I was asleep.

After settling into our rooms in Simatai, we begain our visits to the nearby villages. The first one we visited was Jijiaying, which in ancient times was a military garrison and still has most of its original gates. The impression a place like this gives is one of age——ancient peasants hobbling past ancient cottages; and the villages are aging. The youth have mostly left for Beijing, and however many satellite dishes and telephone wires may be set up in the villages are not enough to give one hope for their future.

After settling into our rooms in Simatai, we begain our visits to the nearby villages. The first one we visited was Jijiaying, which in ancient times was a military garrison and still has most of its original gates. The impression a place like this gives is one of age——ancient peasants hobbling past ancient cottages; and the villages are aging. The youth have mostly left for Beijing, and however many satellite dishes and telephone wires may be set up in the villages are not enough to give one hope for their future. Jijiaying may be ancient and its villagers may be graying, but the ideal of modernity has a powerful appeal there. In the local offices of the Communist Party, a shuzi yingyuan——"digital theater"——had been set up for the villagers to watch DVDs. And through a window of a storage room in the offices, I saw this thing, a 投票箱 or ballot box. Village government in China is very democratic——China has no problem with democracy making local and unimportant decisions——but even here the Party branch secretary has the last word.

Jijiaying may be ancient and its villagers may be graying, but the ideal of modernity has a powerful appeal there. In the local offices of the Communist Party, a shuzi yingyuan——"digital theater"——had been set up for the villagers to watch DVDs. And through a window of a storage room in the offices, I saw this thing, a 投票箱 or ballot box. Village government in China is very democratic——China has no problem with democracy making local and unimportant decisions——but even here the Party branch secretary has the last word. We next visited Sujiayu Village, where we spent a while pretending we could understand the accents of a few old men we tried to interview. Even an hour out of Beijing, you can hear local accents even our teacher couldn't understand. I did understand the man who kept offering me youtiao (a sort of oily and unsweetened flaccid churro) until I accepted; and I understood the three girls who fled behind a grindstone shouting "Foreigner!" when I came to their part of the village. I stuck around, and they got used to me enough to let me take their picture.

We next visited Sujiayu Village, where we spent a while pretending we could understand the accents of a few old men we tried to interview. Even an hour out of Beijing, you can hear local accents even our teacher couldn't understand. I did understand the man who kept offering me youtiao (a sort of oily and unsweetened flaccid churro) until I accepted; and I understood the three girls who fled behind a grindstone shouting "Foreigner!" when I came to their part of the village. I stuck around, and they got used to me enough to let me take their picture.

Our host and guide, Mr. Huaishun Wang, showed us some of the tools used by the local peasants...

...and much to the entertainment of the villagers, sent his American guests out to fetch water.

After a few days of walking around in these villages, the back of my neck was so thoroughly sunburned that I went out and ponied up the 4 kuai for a straw hat. The locals thought it was hilarious to see a white guy wear their kind of hat, but it does keep the sun off while you're grinding  corn.

corn.

corn.

corn. We had hardly been in the village a day when Mr. Wang came up with nicknames for all of us. Holding the bag is the Professor, behind him is the Beauty. Behind me is the Spaceman, and in front of me is Wu Shouji (which means "without a cellphone"; he refuses to buy one). My nickname was Fourth-year Student, which was a bit boring and cumbersome to say, but it could have been worse. In the picture on the right we've caught the fish that would be the next day's dinner. Chinese water doesn't make for healthy fish, but Mr. Wang was a good enough cook that we put aside our worries about mercury content and the strange lesions on the fish we caught.

When I came back to the city, I went to a Yale Club event, where I discovered just how many Yalies are in the city right now, and picked up some free tickets from a promoter of the Yale Philharmonia. Absolutely anything can happen in Beijing--and in just 20 days, things are going to really get started.

Friday, July 11, 2008

家

Last Saturday, I was greeted in my dorm room by Li Jiahao, my 10-year-old honorary little brother in Beijing. Every student in the HBA program was assigned to a family here, but I had the good luck to be put with a family that lives on campus. Mr. Li is an English professor here, and during the school week his family lives in the dormitory across the street from mine. On the weekend they have a much nicer apartment in Huilongguan (where I took the picture at right), but living on campus makes it easier for the Lis to get to work (Mrs. Li is a nurse in the clinic at the School of Mines next door), and for Jiahao to come over to my dormitory. He's a smart kid; he thinks my textbooks aren't difficult enough and from time to time will teach me literary expressions he thinks I ought to know. Right now he's on summer vacation, but he still goes to classes a few days a week to work on his English. When I've been wrangling with Chinese for a while it's a welcome break to help Jiahao understand the vagaries of English irregular verbs.

Last Saturday, I was greeted in my dorm room by Li Jiahao, my 10-year-old honorary little brother in Beijing. Every student in the HBA program was assigned to a family here, but I had the good luck to be put with a family that lives on campus. Mr. Li is an English professor here, and during the school week his family lives in the dormitory across the street from mine. On the weekend they have a much nicer apartment in Huilongguan (where I took the picture at right), but living on campus makes it easier for the Lis to get to work (Mrs. Li is a nurse in the clinic at the School of Mines next door), and for Jiahao to come over to my dormitory. He's a smart kid; he thinks my textbooks aren't difficult enough and from time to time will teach me literary expressions he thinks I ought to know. Right now he's on summer vacation, but he still goes to classes a few days a week to work on his English. When I've been wrangling with Chinese for a while it's a welcome break to help Jiahao understand the vagaries of English irregular verbs. The Li family has very much taken me under their wing, and lavish attention on me in a way I doubt an American family would do. They've invited my whole family, for example, to come to Beijing and stay at their home in Huilongguan, and they fairly regularly invite me to dinner or bring homemade food to my dormitory. When I finish writing this, Mrs. Li has offered to teach me how to make dumplings.

The Li family has very much taken me under their wing, and lavish attention on me in a way I doubt an American family would do. They've invited my whole family, for example, to come to Beijing and stay at their home in Huilongguan, and they fairly regularly invite me to dinner or bring homemade food to my dormitory. When I finish writing this, Mrs. Li has offered to teach me how to make dumplings.In my temporary Chinese family, there are two other HBA students, both from second-year, but a language barrier even more severe than mine and a considerably more burdensome workload leave them less time to spend with our Chinese family. At the beginnging of the program, my fourth-year-classmates and I were given a whole song-and-dance about how difficult the work would be, but to be honest, it hasn't been bad at all. I'm good enough at Chinese that the language pledge doesn't mean a vow of silence, and compared to the rather insane life I built for myself at Yale, a 400-character essay a day is nothing.

And if I should ever get bored or discouraged, the Li family is more than happy to feed me. Food is tremendously important to the Chinese: I don't know whether this is necessarily true, or whether the Chinese appreciate fine dining more than other nations, but it is a stereotype that has become a part of Chinese self-consciousness. "民以食为天," Mr. Li will often say to me at the start of a meal. It's a 2000-year old aphorism: "The people regard food as heaven." Another favorite aphorism of Mr. Li's is "吃饱了, 不想家": "When you've eaten your fill, you won't miss home." Of course I miss home; I miss my family, and yesterday I went on a shopping spree for milk and cheese (cheese is phenomenally expensive in Beijing, but it can be had). But the Li family do a pretty good job of filling the gap, whether giving me the occasional piece of fruit or taking me out for a full-blown Beijing hot-pot dinner. Tomorrow Mr. Li is taking me to his co-worker's wedding; but I doubt I'll have time to post on it before I leave for the countryside Sunday morning.

And if I should ever get bored or discouraged, the Li family is more than happy to feed me. Food is tremendously important to the Chinese: I don't know whether this is necessarily true, or whether the Chinese appreciate fine dining more than other nations, but it is a stereotype that has become a part of Chinese self-consciousness. "民以食为天," Mr. Li will often say to me at the start of a meal. It's a 2000-year old aphorism: "The people regard food as heaven." Another favorite aphorism of Mr. Li's is "吃饱了, 不想家": "When you've eaten your fill, you won't miss home." Of course I miss home; I miss my family, and yesterday I went on a shopping spree for milk and cheese (cheese is phenomenally expensive in Beijing, but it can be had). But the Li family do a pretty good job of filling the gap, whether giving me the occasional piece of fruit or taking me out for a full-blown Beijing hot-pot dinner. Tomorrow Mr. Li is taking me to his co-worker's wedding; but I doubt I'll have time to post on it before I leave for the countryside Sunday morning.Thursday, July 10, 2008

The Thirteen Tombs

Last Saturday I went on a classic tour-bus excursion to the 十三陵,the Thirteen Tombs of the Ming Emperors. The tombs are technically within Beijing Municipality, but they're far enough out from the city center that they're surrounded by farmland. It's a nice place, and of course one with a lot of history, but not interesting enough to be worth more than a few pictures:

The 神道 or Divine Path leading to the tombs is protected by a menagerie of stone animals, including this fantastic beast. Somewhere out there is photographic evidence of me riding one of the stone horses, but before I could get my own camera out we were confronted by a couple of less-than-amused gardeners.

Here's me in front of the Changling, which if I remember right is the tomb of the Yongle Emperor Zhu Di. The building behind me, called the 明楼 (which for some reason is usually translated Soul Tower), isn't actually the tomb. Behind the tower is an enormous earth mound, under which Zhu Di is doing whatever dead Ming emperors do.

The Dingling (however silly it sounds in English, it means the Stable Tomb), is the only Ming tomb to have been officially excavated. Unfortunately, it was excavated just prior to the Cultural Revolution, so most of its contents, including the Wanli Emperor himself, have been destroyed. Just visible in the background of this picture is the freshly painted replica of the emperor's red coffin; the official plaques, pointing out that the coffin was a replacement, somehow neglected to mention anything about Red Guards. This tomb is a little more than 50 feet below ground, so it was a cool and damp alternative to the muggy surface.

The 神道 or Divine Path leading to the tombs is protected by a menagerie of stone animals, including this fantastic beast. Somewhere out there is photographic evidence of me riding one of the stone horses, but before I could get my own camera out we were confronted by a couple of less-than-amused gardeners.

Here's me in front of the Changling, which if I remember right is the tomb of the Yongle Emperor Zhu Di. The building behind me, called the 明楼 (which for some reason is usually translated Soul Tower), isn't actually the tomb. Behind the tower is an enormous earth mound, under which Zhu Di is doing whatever dead Ming emperors do.

The Dingling (however silly it sounds in English, it means the Stable Tomb), is the only Ming tomb to have been officially excavated. Unfortunately, it was excavated just prior to the Cultural Revolution, so most of its contents, including the Wanli Emperor himself, have been destroyed. Just visible in the background of this picture is the freshly painted replica of the emperor's red coffin; the official plaques, pointing out that the coffin was a replacement, somehow neglected to mention anything about Red Guards. This tomb is a little more than 50 feet below ground, so it was a cool and damp alternative to the muggy surface.

Wednesday, July 2, 2008

我买了车了

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

Evening at Tiananmen

It was a cool evening and pleasant as I wove my way through the construction on Chengfu Rd. The friends I might have wanted to eat dinner with were away or busy or not answering their phones, and the prospect of writing an essay on one of three equally uninteresting topics was enough to get me out of my room fast. The idea had come into my head——who knows from where——that instead of getting dinner I should visit Tiananmen Square, and almost without realizing it I found myself on my way to the train station.

It was a cool evening and pleasant as I wove my way through the construction on Chengfu Rd. The friends I might have wanted to eat dinner with were away or busy or not answering their phones, and the prospect of writing an essay on one of three equally uninteresting topics was enough to get me out of my room fast. The idea had come into my head——who knows from where——that instead of getting dinner I should visit Tiananmen Square, and almost without realizing it I found myself on my way to the train station.To get to the Square I would have to change trains twice, but Beijing's subways are clean and modern, at least by comparison with New York's, and the trip was much less of an ordeal than I had been warned riding the Beijing metro could be. As with everything about Beijing, the most impressive thing is the size: to change trains at Xizhimen, I had walk through a seemingly endless series of tunnels and passages and covered walkways, including a massive underground hall inexplicably designed in the style of an Egyptian temple. On all but the oldest line, subway announcements were made in both Chinese and English, and the whole thing felt strangely familiar, but it's hard to imagine that the delightful sign warning me not to hold the doors open with my hand could appear in New York.

When I arrived at Tiananmen West Station, I was greeted by all the minorities of China, who apparently are surpassed in their delight over Beijing's Olympics only by Wanglaoji Tea. Olympic-themed advertisements are everywhere on the Beijing subway (A video ad informed me that Snickers was the official supplier of chocolate to the Games). But this one's as good as it gets. It's a commercial advertisement that perfectly represents the party line of China's 56 races in harmony, and despite the fact that Wanglaoji is not an Olympic sponsor——the Olympic logo is nowhere on the poster, nor are the Games directly mentioned——it manages to get in on the hype of the posters all around it. The ad is a perfect fusion of politics and commercial opportunism, and may be the best summary of this country's approach to the Games that I've seen yet.

When I arrived at Tiananmen West Station, I was greeted by all the minorities of China, who apparently are surpassed in their delight over Beijing's Olympics only by Wanglaoji Tea. Olympic-themed advertisements are everywhere on the Beijing subway (A video ad informed me that Snickers was the official supplier of chocolate to the Games). But this one's as good as it gets. It's a commercial advertisement that perfectly represents the party line of China's 56 races in harmony, and despite the fact that Wanglaoji is not an Olympic sponsor——the Olympic logo is nowhere on the poster, nor are the Games directly mentioned——it manages to get in on the hype of the posters all around it. The ad is a perfect fusion of politics and commercial opportunism, and may be the best summary of this country's approach to the Games that I've seen yet.When I came up from the subway, I found out I had just missed the end of the flag-lowering ceremony. As I came onto the Square, the last soldiers were marching away from the flagpole, and the crowds of tourists and this was a Monday were slowly dispersing. But Tiananmen Square is impressive enough even without pomp and circumstance. The Great Hall of the People is designed on such a gargantuan scale that I could only tell its size by looking at the workers sweeping water off the steps with branches. In the middle of the Square is Mao's tomb, and against the fog I could make out remnants of the ancient fortifications that had survived his urban planning schemes.

As I took this shot, an elderly man passed by me, explaining to his grandson that Tiananmen Square was where Mao first proclaimed the foundation of the People's Republic of China. The car in the foreground pulled up while I was fiddling unsuccessfully with the focus, and where once Mao decried capitalism and the United States to masses of Red Guards, an impeccably-dressed businessman stepped out of a Chevy and took his own pictures.

请勿入内: Do Not Enter.

Everyone talks about how China has changed, but at least on a Monday night, the Forbidden City is as forbidden as ever.

Before I got back on the subway, I took a brief detour to Zhongnanhai, the Forbidden City of the New China, where the chiefs of the Communist Party do whatever it is they do. The Forbidden City next door distracts a lot of attention from Zhongnanhai, which is probably not unintentional, but this is where the government of China really happens:

And lastly, this lame little clip which I made to prove that I went to Tiananmen, but mainly to test the video function of my camera:

(Some of these pictures have been touched up considerably; the lighting conditions on Tiananmen Square Monday night were awful.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)