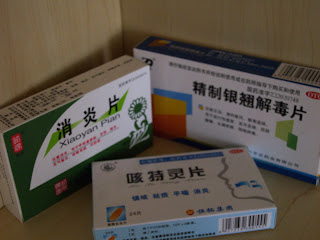

At this 药房, I explained my symptoms to one of the pharmacists on duty, who promptly gave me three types of pills, explaining that I had "rising fire" in my throat. I tried to get a more Western diagnosis, but the pharmacist would have none of it. I had "rising fire" in my throat, and these, she insisted, were the best medicines for it. Readers of the Foreign Devil, don't get the impression from this story that I had walked into some magician's hole-in-the-wall to buy medicine. The facility was clean and spotlessly white, with the medicines neatly displayed in glass cases. In China, there has been a very big movement to try to legitimize the traditional medicine with the trappings of Western medicine, and my "rising fire" was diagnosed by a woman in a neat white lab coat. When I got back to the dormitory, I rummaged through my dictionary and discovered that I had been sold "Antiphlogistic Tablets," "Refined Honeysuckle-Forsythia Antitoxic Tablets," and "Supereffective Cough Tablets," but unfortunately very few of the characters on the ingredients list were in my dictionary. I managed to translate them online, and to my disappointment I found the pills were mostly made of various fairly innocuous plants. I had been half expecting fillet of a filly snake or something like that. Since then I've been taking the pills and feeling better, so it may be that they've successfully put out my "rising fire."

At this 药房, I explained my symptoms to one of the pharmacists on duty, who promptly gave me three types of pills, explaining that I had "rising fire" in my throat. I tried to get a more Western diagnosis, but the pharmacist would have none of it. I had "rising fire" in my throat, and these, she insisted, were the best medicines for it. Readers of the Foreign Devil, don't get the impression from this story that I had walked into some magician's hole-in-the-wall to buy medicine. The facility was clean and spotlessly white, with the medicines neatly displayed in glass cases. In China, there has been a very big movement to try to legitimize the traditional medicine with the trappings of Western medicine, and my "rising fire" was diagnosed by a woman in a neat white lab coat. When I got back to the dormitory, I rummaged through my dictionary and discovered that I had been sold "Antiphlogistic Tablets," "Refined Honeysuckle-Forsythia Antitoxic Tablets," and "Supereffective Cough Tablets," but unfortunately very few of the characters on the ingredients list were in my dictionary. I managed to translate them online, and to my disappointment I found the pills were mostly made of various fairly innocuous plants. I had been half expecting fillet of a filly snake or something like that. Since then I've been taking the pills and feeling better, so it may be that they've successfully put out my "rising fire."But yesterday afternoon, I still was plenty stuffed up, and I decided to use my own way of dealing with a cough——I would go for a run. Generally I can breathe more easily after a long run—I think that a run forces my body to demand enough oxygen from my lungs that they give up the struggle and clear themselves out. And after the first block or two (where I was sounding terrifically tubercular), I was breathing fine, pollution or no pollution. I set off east along Zhixin Lu, passing one or two Chinese schoolchildren who were as proud of greeting me in garbled English as I was of responding in garbled Chinese.

And then, just after I had crossed over the Badaling Expressway, I first caught sight of it. The fog in Beijing was particularly bad yesterday, and anything more than half a block away was half-obscured by the mist. But there, dominating the horizon, waiting like the cocoon of some monstrous insect, was the shadow of the Olympic Stadium, visible even from a half-mile away. I ran up as close as I could to it, but the Olympic compound was only open to VIPs and construction workers, and thin lines of official black cars and dirty trucks streamed in and out of the security checkpoints in the fence.

But behind the fence, and behind the aquatics center, was the reason for the whole business. I've always thought the stadium was an ugly thing, and part of me still does, but it doesn't need to be beautiful. Half-seen through the fog, the building made its presence felt as something massive. There behind that fence was a great and terrible testimony to the combined might of the Chinese people and to the will of their State. I looked at it, and my jaw dropped, and I didn't care that the Chinese were watching my amazement. It was an almost religious awe, what a peasant might have felt who in earlier times found himself by chance catching a glimpse through the gates of the Forbidden City. And always there was activity: guards patrolling, credentialled persons pouring in and out, and the workers, small leathery men from the farthest corners of China, squatting with their lunches on the curb.

I turned left on Beichen Xilu and found myself running alongside a seemingly endless fence, with guards both inside and out. The guards outside the fence were what I've become used to seeing all over China. They are always slight men, and their emaciated frames are exaggerated by uniforms that are always at least a size too big. Their uniforms are dull green, in a shade that always looks dirty, and I've never seen them carry a weapon more intimiating than a walkie-talkie. The guards inside the fence were not bigger men, but they had guns, and Soviet-style military caps, and epaulettes, and gold stripes on their uniform pants, and most of them had puffed their chests out so far they could hardly breathe. They stood against the background of the mist-shrouded buildings of the Olympics, an allegory of the Games and of their country.

When after a little less than a mile in that direction I decided to head back, I found myself running by the Olympic Village, just receiving the finishing touches before the Games. Here, in a few weeks, would live the greatest athletes in the world; this was the backstage for the greatest public drama anyone will have seen in years. But now the dormitory buildings were lifeless and identical, stretching away in long forbidding aisles until they were lost in the fog. I couldn't enter this compound either; it had its own fences and checkpoints, and I had to wait till I had passed the whole Village before I could turn west. At that intersection, an inscribed stone reminded passers-by of the Olympic motto, "One World, One Dream." 同一个世界,同一个梦想: like some mantra these phrases have been plastered all over Beijing. On T-shirts, on the walls of buildings, on banners, on bumper stickers, on beer bottles, the phrase is repeated, endlessly and endlessly. Through the fog yesterday, I could see it everywhere, written vertically or horizontally, carved in stone or painted in garish colors. "One World, One Dream."

The fence of the Olympic Village was, unlike most of the Olympic construction, actually quite attractive, a sort of combination of Art Deco and Chinoiserie (Chinese architecture has Westernized to the point where it's not silly to speak of Chinese Chinoiserie). Within the fence the motto was everywhere. And on every fence post, it was alluded to. But for some reason, probably some fortuitous mistake, the order was reversed. The square and solid pillars of the fence each read "Dream / World / 2008," and the words became the rhythm of my steps as I ran through that dream world, past dormitory after dormitory and gate after gate. Long after the Olympic Village had been left behind in the fog, after I returned to my dormitory for another dose of mysterious herbs, I was still in the Dream World of Beijing 2008.

3 comments:

You're taking those meds??! o_O

Kevin, if you die of anything other than a gunshot wound (pollution, ingested chemicals, getting beaten by unarmed guards as you snoop around) your readers will be most disappointed!

Fear not, esteemed Readers. If I die in China, I will be sure to do so in interestingly enough to merit a truly wonderful blogpost.

well then, that's all we can truly ask of you (i'm not anonymous)

beautiful storytelling as always :)

Post a Comment